The Opening of Niverville's Cultural/Historical Museum on September 30, 2021 -- Part 2

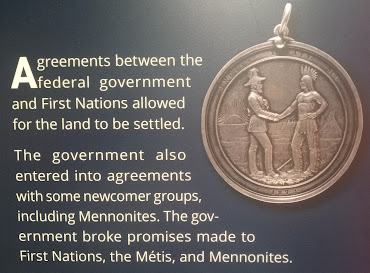

In Part 2 of this article, we will take a look at how these three people groups--First Nations, Métis and Mennonite--were all people of faith who believed in the Creator whose authority transcended that of the authority of nation-states such as the Canadian Government that sought to exercise "power over" territory and people that they had not sufficiently established relationships and personal knowledge of before they tried to occupy and colonize the land.

No other nation would put up with this type of non-relational, impersonal occupation of territory by a foreign power, but apart from a few skirmishes in 1870 and 1885, by far the most Métis and First Nations did not resist militarily. Why was this so? Because they gave their word. Three of the seven original teachings of Native Spirituality were Respect, Honesty and Truth-telling. The Creator is one who keeps His promises, and in order to reflect Him accurately, so must we.

The First Nations Had Faith in the Creator Above

The above words given by Elijah Harper in his opening remarks at the Sacred Assembly in December of 1995 are prominently inscribed on a panel at the Niverville Museum for all visitors to read. The words taken from his original speech had to be condensed, but in his full statement, he declared, "I have a vision for this country we call Canada...It is a vision that lies in the heart and soul of our people...Above all, this vision embraces the supremacy of God our Creator, and is inherent in the treaties that were made with the newcomers that came to this land..."

These statements are interspersed within a larger context of his opening speech at the Sacred Assembly in December of 1995. In order to hear a longer 2 1/2 minute context of this speech, you can listen to it here. In the discussion of First Nations Elders that took place after the end of Elijah's opening speech you will hear one elder say with emphasis that "there is only one God, one Creator up above!"

One of the most salient points in the Reconciliation Proclamation that came out of Elijah Harper's Sacred Assembly was the statement that the Creator is a personal God: "We share an understanding that the starting point for healing and reconciliation lies in personal communion with the Creator God."

Nor is the belief in one Creator simply Elijah Harper's vision, but it is the vision of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) of Canada in their Declaration Statement.

Rupert's Land was a large tract of land that comprised all of the territory of rivers that ran into the Hudson Bay, a territory that King Charles II of England appropriated unto himself for the purposes of the fur trade, and unilaterally placed his cousin Prince Rupert as the Governor over this entire region.

The Métis had learned, over time, to tolerate the government of the Hudson Bay Company, and to generally get along as they intermarried between European and First Nations ancestry. However, just as there was tension between the English and the French for supremacy in Eastern Canada, there was tension between the Hudson Bay Company and the North West Company for supremacy over Rupert's Land. The tension was more between the British HBC and the French NWC rather than between either of those trading companies and the original people of the land. In fact, Native chiefs like Peguis used all of his diplomatic and negotiating skills as one who listened before he spoke in order to keep the peace between them.

Of course, it was impossible for the Hudson Bay Company to enforce a monopoly in areas where it had no presence, so there was tension between the HBC and the NWC until 1821 when the two companies merged.

The above map illustrates why the HBC had the upper hand, even though they had many challenges as well with some 30 portages needed within the network of their "river highways" into the Hudson Bay, whereas the NWC had many more portages and challenges along the arduous land route into and through Eastern Canada before they could reach sea water.

However, neither company could make a profit if they spent their resources competing with each other. So the two companies amalgamated in 1821. Then on March 20, 1869, the Hudson's Bay Company reluctantly, under pressure from Great Britain, sold Rupert's Land to the Government of Canada for $1.5 million, and the possession date was to be December 1 of that year.

For the Métis to be simply told that now in 1869 that there was a new authority that they had no knowledge about that governed the land that they lived on for so long was understandably very alarming news. When the Government of Canada started to send out their survey crews with their chains to section off the land even prior to December 1, on October 11, 1869, a mounted patrol of nineteen unarmed Métis, led by Louis Riel, confronted a Canadian government survey crew and compelled it to withdraw.

By October 16, 1869, the Red River Métis formed the National Committee of the Métis, and called for an independent Métis republic. They were able to block the Canadian Government's taking possession of Rupert's Land by December 1, 1869, and by December 8, 1869, they formed a Provisional Government that was eventually led by Louis Riel.

On that same day, this Métis Provisional Government made a Proclamation that they called a Declaration of the People of Rupert's Land and the North-West that was signed by John Bruce, president, and Louis Riel, secretary. The complete Declaration can be read here.

It is important to note that the appeal of this Métis Provisional Government was to the "God of the Nations" as a higher Authority than that of the Canadian Government.

"We, the representatives of the people, in Council assembled in Upper Fort Garry...after having invoked the God of Nations, relying on these fundamental moral principles, solemnly declare, in the name of our constituents, and in our own names, before God and man, that, from the day on which the Hudson Bay Government we had always respected abandoned us, by transferring to a strange power the sacred authority confided to it, the people of Rupert's Land and the North-West became free and exempt from all allegiance to the said Government. Second. That we refuse to recognize the authority of Canada, which pretends to have a right to coerce us, and impose upon us a despotic form of government still more contrary to our rights."

I find it of interest that in the Niverville Museum which was opened on September 30, 2021, that right above the Statement by Elijah Harper proclaiming "the supremacy of God our Creator," that we have a picture of Louis Riel's Provincial Government members of 1869 who also invoked the supremacy of "the God of Nations" in their Declaration of the People of Rupert's Land and the North-West. This Declaration is what led to the negotiations led by Louis Riel on behalf of the Métis with the Canadian Government which led to the Canadian Parliament passing the Manitoba Act on May 12, 1870.

The above statement of Louis Riel in 1885 is documented at the Niverville Museum. "All that I have done and risked...rested certainly on the knowledge that I was called upon to do something for my country. I know that through the grace of God, I am the founder of Manitoba." So Louis Riel not only appealed to the "God of the Nations" for ultimate justice, but he attributed his part in founding Manitoba to "the grace of God."

It is this reality that enabled Louis Riel to state before his death that "I have always believed that, as I have acted honestly, the time will come when the people of Canada will see and acknowledge it."

Louis Riel's legacy as the founder of Manitoba is further recognized at a statue of him that has been erected adjacent to the Provincial Legislature in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Just prior to his execution on November 16, 1885, he declared that "In a little while, it will be over. We may fail, but the rights for which we contend will not die."

Then, with some of his final words in his own hand-writing, he reveals where his unshakeable faith was placed. "I must speak of God in whom I trust. In him I have rom to hope. The rope Threatens my life, but Thank God, I fear not."

In the summer of 1986, just over 100 years after Louis Riel's death on November 16, 1885, I took a group of Métis from northern Saskatchewan to the site of Louis Riel's grave in the cemetery of the St. Boniface Cathedral in Winnipeg. These Métis were personal friends of mine, and they just stood there in silence for a long time without saying a word.

Then I could see tears begin to stream down their faces. I could tell that Louis Riel's story had a direct connection to their heart, and they were feeling the unhealed pain. It is interesting that by Oral Tradition, the statement is attributed to Louis Riel that "My people will sleep for 100 years, but when they awake, it will be the artists who give them their spirit back." This has been happening.

In view of the huge wound and scar that Louis Riel's death made on Canadian History, it is significant that those of us who are Niverville residents that Lucy Guiboche spoke at Niverville's 50th Anniversary Celebration on September 8, 2019. As a respected Métis Elder who is on the Mayor of Winnipeg's Indigenous Advisory Circle, she spoke blessing over the land in our area. The significance of this blessing is also noted in our Niverville Museum, where Lucy's are also prominently displayed. "As a Métis Elder honoured to have spoken at Niverville's fiftieth anniversary celebrations in 2019, I pray the Creator's blessing on the descendants of the pioneer Mennonite, English, and Scottish settlers and for ongoing healing."

Métis Elder Lucy Guiboche also blessed both the people and the land around Niverville and vicinity at a special event on July 1, 2022, on Canada Day. She spoke straight from her heart and her words were well received. The report on that July 2, 2002 event will be the topic of another post that is documenting Niverville's Journey towards Reconciliation. In the picture below, Lucy Guiboche is the third one standing from the left which pictures Métis along with Niverville Mayor Myron Dyck at the Community 2022 Canada Day Celebration.

The Mennonites Overcame Huge Challenges in Proving that this Land was Suitable for Agricultural Purposes Through Courage and Faith in the Creator

The earliest immigrants in the Niverville area did not come to an area that was suitable for farming, but the East Reserve (the present-day Rural Municipality of Hanover) was a land filled with many swamps that needed to be drained, and sticks and stones that needed to be removed. The Niverville Museum acknowledges the faith and sacrifice of these earliest settlers.

Acknowledgment of the faith and sacrifice of the earliest settlers, particularly the Mennonites, is also recognized in other Historical Markers in and around Niverville.

The Mennonite Memorial Landing Site of the first Mennonite settlers to the East Reserve in Manitoba on August 1, 1874, acknowledges that "these Mennonite men and women were among the first Europeans to establish farm communities on open prairie. They also became known for successfully transplanting their nonresistant, church-centered ways of life. We gratefully acknowledge their bequeathal of courage and faith in God."

Some 7,000 Mennonites who were experiencing resistance and opposition to their faith in south Russia landed here between 1874 and 1880. From this site, many walked to the site of the Shantz Immigration Sheds which was a staging area eight kilometres to the East from where they were assigned their property in what is today the Rural Municipality of Hanover. The most fragile, including mothers with babes in arms, as well as the freight, were taken from the Landing Site to the Immigration Sheds by the Métis in their Red River Carts.

The Métis Red River Cart became a symbolic connecting link between the pre-settlement and post-settlement era, and is a direct link between the Mennonite migration of the 1870s and the Métis story of Manitoba.

The ancestry of present-day residents of Niverville such as Brenda Neufeld Lapointe are a living example of this Métis-Mennonite (the M and M) Connection in our local history. Brenda's 5th generation grandfather was a brother to Peter Garrioch, a Métis trader who pioneered the construction of the Crow Wing Trail back in 1844, and it was this same Métis trader who also took Brenda's great grandparents on her Mennonite side from the Mennonite Landing to the Immigration Sheds in his Métis Red River Cart back in 1874.

In the words of Brenda Neufeld Lapointe, "I have 100% Russian Mennonite ancestry on one side of my family, and 100% Métis ancestry on the other side of the family. When I was a young girl at home, our dinner conversation went like this. My dad would say, 'My grandparents walked all the way from the Red River Mennonite Landing Site to the Immigration Sheds!' My mom would say, 'That's not true! My uncle gave them a ride!'"

The map above shows the relative locations of the Mennonite Landing Site at the junction of the Red and the Rat River, and the location of the Schantz Immigration Sheds, and the location of the Community of Niverville to the north and west of those sheds. From the Immigration Sheds, the Crow Wing Trail followed a path that runs right through Hespeler Park in Niverville.

Hespeler Park in Niverville is named after William Hespeler (1830-1921), a German businessman and immigration agent who played a key role in the settlement and development of Western Canada. As an Immigration Agent for the Canadian Government, he recruited some 7,000 Mennonites to eventually come to Manitoba between 1874 and 1880 in one of the first large waves of European migration to the West. These pioneers inspired many other groups to settle the Prairies by demonstrating its enormous agricultural potential.

The Stone in front of the sign marking the entry way into the Hespeler Park bears a plaque which reads: "THIS STONE STANDS...as a memorial to the thousands of Mennonite settlers who helped pioneer this region during the 1870's. The character, prosperity and development of the Southeast, including the Town of Niverville, takes its inspiration from these courageous, hardworking people of faith."

So here we have triple confirmation that it was the FAITH of these earliest settlers that gave them the courage to persevere, to endure, to stand firm and to keep going in facing many formidable obstacles in demonstrating that this land could not only be suitable for agriculture, but that there would be an overflow that would enable this area to feed the hungry in other parts of the world.

First, the cairn at the Mennonite Landing declares, "We gratefully acknowledge their bequeathal of courage and faith in God." Second, the tribute to the earliest settlers at the Niverville Museum declares that "through faith and sacrifice they laid the foundation for our heritage. May their memory inspire future generations." Finally, the cairn at the entry way to the Hespeler Park proclaims that the Southeastern part of Manitoba, including the Town of Niverville, "takes its inspiration from these courageous, hardworking people of faith."

To say that these pioneers whether Mennonite, Métis or First Nations did not also have an element of religion and religious control come into their communities, especially through the institutional and denominational church into their spirituality and faith in the Creator would be to turn a blind eye to the realities of our history. Religion has brought in an element of legalism and domination based on the fear of punishment into these faith communities, and this is where I put it to you that the image of the Creator has been misrepresented, caricaturized and distorted.

This is why both the political process which led to the Indian Act in 1876, and the religious process which led to the policy of the Federal Residential Schools in about 1883 have failed us, and it is also why Elijah Harper said that "what has been missing is the spiritual element." A spiritual element of "personal communion and knowledge of the Creator is needed," a knowledge that is not based on fear and control, but rather on love and on personal relationships.

For example, if one looks at the layout and design of the interior of the St. Peter's Church that Chief Peguis attended, you can see that the facility was not conducive to intimacy, but the clergyman or preacher stood up on a pedestal high above the congregation who mainly listened, but did not hardly get a chance to speak, and this design is contrary to building connections in a relational way.

Notice how high and aloft and preacher/clergyman stood in his pulpit over and above those sitting in the pews. It put the speaker into an exalted position, and it was the one who had the pulpit who had the voice, and if it was as true here as it was in most denominational churches, during services the people had neither voice or opportunity to engage, or to interact in a meaningful way in order to properly process what was said.

While Chief Peguis wanted teaching from the word of God to always be spoken on his land, yet the process of discipleship requires something more than the lecture or the sermon. It requires interaction, questions and answers where everyone has something to teach and to learn. What Chief Peguis would have been familiar with in his tribal councils was that the chief would sit in a circle among the other tribal elders, and the practice was that each would wait their turn to speak, but would provide a listening ear to all of the others in the circle. A good chief like Peguis would first of all listen to the others before making a decision, a decision that would only come after the others in the circle had felt heard and listened to.

A skilled hunter and diplomat, Chief Peguis worked to protect the rights and interests of the Anishinaabeg of Red River. He stepped in to save lives when fur trade animosities threatened the Selkirk Settlement. During an era of fur trade hostility and ecological disasters, Chief Peguis deftly balanced Anishinaabe interests with those framed by their relationship with the Hudson's Bay and their entrepreneurial Métis neighbours."

Even the circle in the middle of the flag of the Peguis First Nation (formerly St. Peter's Band). The red circle in the middle speaks of the circle of life, and the circular nature of the tribal council in which everybody could share in turn and ask questions in contrast to the elevated and lofty pulpit in St. Peter's Stone Church from which the clergy would be speaking down to the people from an elevated position. A real connection can really only happen in smaller groups where people can both give and receive, and in a context where all are seen, heard and valued so that heart connections can happen.

What we are saying is that for people to really get to know one another from the inside out and to connect at a heart level, at some point interactive conversations and an engaging with one another is absolutely necessary. In a day of great advances in technology and scientific knowledge, intimacy and personal knowledge of people that we do not really know is lacking a lot in Canadian society as a whole today, and this has also been the case in our history.

Our prayer is that through interactive conversations and heart-to-heart sharing, Niverville will increasingly become like "a city set on a hill," a light in the midst of that darkness by walking in the light together with others. Greater intimacy and a personal knowing of one another cannot happen in an atmosphere of harshness, of judgment, of finger pointing, of blaming. True maturity comes with an acceptance of responsibility for our own errors, and a believing of what is best in others so that we all can change from the inside out. This is what true transformation is all about.

So there are definitely some roots in Niverville's history that need to be severed, religious roots that have produced in many cases the fruit of isolation from one another, evil speaking of people that we do not know, judging others by their actions but ourselves only by our intentions. We need to "lay the axe to the root" of those types of patterns that they will not bear fruit in future generations. Yet spiritually, the fact remains that we believe that we all came from one Creator, a Creator who is good and trustworthy, and who created us in His image to reflect His goodness and faithfulness to His promises to those who trust with endurance during times of testing.

The fact is that there are many good roots in our history in Niverville that should not be discarded by any means. Our ancestors have left us a legacy of faith, courage, generosity and goodwill, even in the midst of trials and testings. This should be both a challenge and an inspiration to us to continue that legacy and that tradition. Ever since the post-settlement era, Niverville's history ever since 1878 is closely associated with grain.

The hardiness and determination of the early settlers, coming from a harsh environment in South Russia ensured that this unforgiving land would be transformed into a place from which livelihoods could be wrested, albeit with considerable effort and cost. The settlers in the East Reserve had all pursued farming, and in the year 1878, 9,416 acres of land were under cultivation, which that year produced 196,090 bushels of grain.

Niverville is a community of many firsts. It was the first Mennonite settlement in Manitoba although it was cosmopolitan from the start, and it was a point from which the settlers began other communities. It was the site of the first grain elevator in Western Canada. It was a supplier of the first western Canadian barley ever shipped privately to an overseas market. Its farmers were among the first to recognize the importance of a decentralized agricultural industry. In later years, these generous settlers sent grain in relief to others suffering from famine in Russia.

Even to this day, local farms such as Artel Farms and farmers such as its owner Grant Dyck have demonstrated a heart to strengthen that legacy of generosity, and to embrace the responsibility to both "respect the land, and to share in the harvest." This is demonstrated in such charitable initiatives as the Grow Hope Project which is doing its part to address world hunger in cooperation and collaboration with the Canadian Food Grains Bank.

It needs to be cherished and valued that the settlers who have chosen to establish their roots in

Niverville and vicinity have been a generous people, right from the early

settlers who sent grain in relief to others suffering from famine in Russia, to

the present-day Grow Hope Project being sponsored by the Canadian

Food Grains Bank in order help feed the hungry in other parts of the world

where there is starvation and famine.

This is Niverville in the year 1900 as it has been so beautifully painted on the rear wall of the Niverville Museum. We are forever connected to those who have gone on before us. Many of us have lived in houses in this community that we did not build. We have drunk the water from wells that we did not dig. We have sat under the shade the trees that we did not build. Our overall economy has benefitted from the backbone of agriculture and farmers who, along with the pre-settlement people, were connected to the land that we all share, and on which we all live.

A people without a knowledge of their past history, origin and culture in like a tree without roots!

Comments

Post a Comment