Niverville's new Community Resource and Recreation Centre is a community project that has been made possible by the generous contributions of local Residents, Businesses, the Town of Niverville, the Provincial Government of Manitoba and the Federal Government of Canada. One of the Federal Government's stipulations before they would commit to providing grant money was to insist that a Cultural/Historical Space be made in this building to honour the history of both pre-settlement as well as post-settlement people groups that have had a connection to the land that we live on both in and around the present-day community of Niverville.

The Town of Niverville subsequently hired Joseph Wiebe, an Associate Professor of Religion and Ecology in Ethics and Global Studies at the University of Alberta to organize the Cultural/ Historical Space along with a local ad hoc committee of interested volunteers.

On July 1, 2021, with covid restrictions still in place, the new Niverville CRRC was officially opened with a ribbon cutting ceremony that involved just a small number of community and provincial leaders, but at that point the Cultural/Historical Space was not yet completed.

This Cultural Space was ready to be unveiled and officially opened until September 30, 2021, and this has led to a series of events in Niverville that have contributed to a greater understanding of our history from 1) the unveiling of the museum on September 30 until 2) the unveiling of a Métis Red River Cart as symbolic of a connection between pre- and post-settlement peoples on December 4, 2021, to 3) the unveiling of a cairn at the site of the Shantz Immigration Sheds on May 12, 2022, to 4) the rolling out of the Métis Red River Cart to a special site next door to the Niverville CRRC under a timber frame on July 1, 2022.

One early historic account of the community of Niverville aptly puts our past into a nutshell in the following words: "Named after a French nobleman (Chevalier Joseph-Claude Boucher de Niverville), its site was chosen by an Englishman (Joseph Whitehead), planned by a German businessman (William Hespeler), settled by Mennonite, English and Scottish farmers, and partly developed by Jews."

The earliest Mennonite settlers simply wanted to preserve their church-centred ways of life, and so they lived in block settlements such as the East and West Reserves. While Niverville was a "gateway" community into the East Reserve, the fact that it was on the very north-western edge of that reserve made Niverville more of a cosmopolitan community from the "get-go," resulting in Catholics, Protestants, Jews, English, Scottish and Mennonites living in the same area for nearly 150 years.

While most communities on the East Reserve today are cosmopolitan in nature, I would submit for your consideration that Niverville's unique role in being cosmopolitan from its beginning means that it has a more deeply rooted history of people from different ethnicities and cultures living together in the same community. This could position Niverville to be an even brighter light, a role-model of truth and reconciliation between people from different cultures, different people groups, different languages, different mindsets who have gone deeper in their relationships to the point that we not merely "tolerate" one another, but that we actually celebrate our diversity, recognizing that each culture carries something that the others need.

Even this perspective, however, does not take into account that there were pre-settlement people (First Nations and Métis) who had a connection to the land around Niverville long before Canada became a nation in 1867, or the Province of Manitoba was formed in 1870, or the Settlement Period began in earnest in 1874. It is my belief that by building stronger bridges of understanding between the original peoples of the land and the other immigrant groups who settled here later, that the original people who have a longer connection to the land over many years can be a catalyst in teaching the rest of us how to be more sharing and reconciled in our relationships to each other and to be more connected to the land as well. Recognizing this fact, it has become traditional at public events and in schools nowadays to acknowledge that "we are on Treaty 1 Territory."

Significantly, and not necessarily due to any pre-planning on the human side, it turned out that the Niverville Museum which illustrates our community's cross-cultural roots was officially opened on the very first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation that took place on September 30, 2022.

Niverville's deputy mayor John Funk (whose back is turned on the far right) chaired the opening ceremony of the new museum. He expressed how that at first, he did not see the need for such a space, but now that he saw what was being displayed through this initiative, it was beyond his expectations, and he saw what this could mean towards attracting tourism and creating interest in Niverville's roots among all of the visitors who would in future engage with the new Niverville Community Resource and Recreation Centre (CRRC).

The opening ceremony was expected to be very brief, but when special guest Peter YellowQuill began to share his story, he captured the hearts of the dignitaries and the journalists who were there in sharing his heart and in praying a prayer of blessing in the Ojibwe language on this new museum. Peter YellowQuill, from the Long Plain First Nation in Manitoba, is both a residential school survivor, and a fifth-generation descendant of Chief YellowQuill, a signatory to Treaty No. 1.

Peter's story was so compelling, and his release of forgiveness towards those who had wronged him so moving, that even one of the journalists was moved to tears.

Here Judy Peters of Steinbachonline.com and CHSM 1250 AM radio is interviewing Peter YellowQuill with Niverville Citizen reporter Sara Beth Dacombe, Deputy Mayor John Funk and Town of Niverville Councilor Chris Wiebe in the background.

The actual interview that Judy Peters had with Peter YellowQuill as it was aired on CHSM 1250 AM radio, and as it was posted on Steinbachonline.com can be listened to at this site.

Judy Peters also wrote an article for Steinbachonline.com entitled, Niverville Historical Space Key to Reconciliation. The article can be read at this site.

The article on the event that was published by the Niverville Citizen, and that was written by Sara Beth Dacombe was entitled Truth and Reconciliation Major Theme of Museum Opening, and can be located here.

Among other things, Dacombe reported, "After his remarks, YellowQuill invited everyone in attendance into a prayer of blessing for the CRRC, mentioning a specific thankfulness for the Mennonite people who settled in the Niverville area. He mentioned the tradition of the Mennonite people to be compassionate, to feed the world, and to send their young people into the world to do good."

The Carillon News also reported on the Grand Opening of the Niverville Museum with the following front-page feature in colour.

Yellowquill expressed hope for the future, encouraging each of us to count our blessings, and to take action that will lead to stronger relationships. “We will reconcile,” he said after the opening ceremony. “I have every confidence in your faith as a people. I have every confidence in our faith; the traditional faith and the Christian faith, that we shall meet this obligation that we have to the ones that never made it home. To live, to forgive. That’s how we can honour them.”

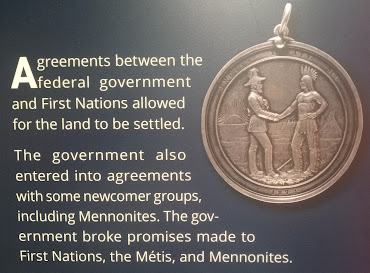

One thing that the First Nations, the Métis and the Mennonites had in common is that all had special treaties and promises made to them by the federal government to address their concerns. This fact is noted at the Niverville Museum. Yet in each case, promises were made with good intentions, but were made only to be broken, and to fall short of expectations.

At the end of the day, these promises were not made between partners who were relationally equal. Seeing themselves as the owners of the land, the federal government basically had a "power over" type of control that enabled them to dominate and to pursue their determined goal of establishing Canadian and British sovereignty over this land from "sea to sea," rather than a "power under" concept of relational government that was there to serve and to undergird and to really get to know the original occupants of the land.

The fact that the Manitoba Act of 1870 failed to adequately address Métis concerns, and that Treaty No. 1 of 1871 failed to be mutually understood in addressing First Nation's concerns, and that the Mennonite Privilegium of 1873 failed to permanently address the primary concerns of the Mennonite settlers is historical information that is featured in the Niverville Museum.

The Manitoba Act (1870) Attempted to Address Métis Concerns

The Manitoba Act was passed by the Canadian Parliament on May 12, 1870, and was enacted on July 15 of that same year. This Act was crafted to address the Métis concerns for the preservation of their language, religion, culture, educational system and protection of the land that they already occupied plus additional acreage. However, the reality on the ground was that there was much hostility towards Louis Riel and his government by the Orangemen because of the execution of Thomas Scott, and the Métis could not get legal title to their lands until Canadian surveyors had finished sectioning the land. This was a job which took years, and while immigrants started coming before these protections were realized or implemented, many Métis left the Province of Manitoba for the North West Territories, many relocating to places like Batoche in the North West.

However, it was The Manitoba Act of 1870 that provided for the admission of Manitoba into Canada as its fifth Province. Since this is an act that was negotiated between the Canadian Government and the Métis Provisional Government led by Louis Riel, it is for this reason that Louis Riel is rightly known and recognized as "the founder of Manitoba."

Treaty No. 1 (1871) Negotiated and Signed to Address First Nations IssuesTo address the concerns of the First Nations people in our region, the Canadian Government signed Treaty No. 1 with the First Nations communities of Brokenhead, Sagkeeng, Long Plain, Peguis, Roseau River, Sandy Bay and Swan Lake at Lower Fort Garry on August 3, 1871. However, there was not nearly enough time to get to know and understand one another deeply enough in order to negotiate this treaty to the point that both cultures fully understood one another relationally on a heart-to-heart basis. For example, according to Elijah Harper, terminology like "ceding" the land was understood by First Nations chiefs to mean that they were agreeable to "seeding" the land for agricultural purposes.

Outwardly, the treaty negotiations may have given the appearance of being between Queen Victoria and sovereign First Nations who already had a system of government and concept of land ownership, but the subsequent Indian Act passed by the Canadian Parliament in 1876 gave strong evidence that the treaties were not seen by the Canadian Government as an arrangement between equal partners. Through the Department of Indian Affairs and its Indian agents, the Indian Act gave the federal government sweeping powers with regard to First Nations identity, political structures, governance, cultural practices and education. It was this Act which gave rise to the Residential Schools that history has proven overall to be a failed experiment with mega consequences.

Right at about the time that the last Residential School in Canada was closing in 1996, Elijah Harper called for a Sacred Assembly in December of 1995 that was held across the Ottawa River from the Parliament Buildings in Hull (present-day Gatineau), Quebec that was attended by 3,000 delegates, including the Prime Minister at the time, Jean Chretien, the Minister of Indian Affairs Ron Irwin, the Grand National Chief Ovid Mercredi, representatives of all political parties, and all denominational church leaders as well as First Nations chiefs, Elders and Youth from right across Canada.

Elijah Harper stated at the opening address of this Sacred Assembly on December 6, 1995, "I have a vision for this country we call Canada. It is not my vision at all. It is a vision of our people, the First Nations. It is the vision of our forefathers. It is a vision that lies in the heart and the soul of our people. It is inherent in our traditional values and beliefs. It is inherent in our philosophy, the way we look at life.

The thinking of signatories to Treaty No. 1 in 1871 such as Chief YellowQuill and Chief Henry Prince, and also Chief Peguis (Henry Prince's father) who signed the Treaty of 1817 with the Selkirk Settlers, it becomes clear that their thinking is in alignment with Elijah Harper's words at the Sacred Assembly in 1995.

Chief Peguis has always been associated with peace and reconciliation. He tried to calm thing down during the HBC-NWC wars. This master diplomat listened patiently, and resisted taking sides in the trade wars, and he came to the defense of the Selkirk settlers who had suffered persecution in Scotland.

When it came to issues that came up about who owned the land, it was Peguis' view that the land belonged to the Great Father, but that it could be loaned to Selkirk for awhile. Peguis argued that the land had never been sold.

The Mennonite Privilegium (1873) and the Promise to Address Mennonite Concerns

The Mennonites were persuaded to come to the East Reserve (the present-day Rural Municipality of Hanover in southern Manitoba) with the promise of land, cultural and educational autonomy and guaranteed exemption from military service. The Canadian Government signed a letter of agreement, a Mennonite PRIVILEGIUM on July 26, 1873. The diplomacy of William Hespeler who was hired by the Canadian Government in 1871 as an Immigration Agent, and the Mennonite PRIVILEGIUM is what attracted some 7,000 Mennonites to migrate from South Russia (present-day Ukraine where their way of life was being suppressed) to southern Manitoba between the years 1874 and 1880.

By 1916, during World War I, one of the most provocative issues in Manitoba was school legislation where changes to educational policies threatened the independence that the Mennonites had negotiated under the PRIVILEGIUM. At the Mennonite Village Museum in Steinbach, Manitoba, the following statement that drew attention to the Canadian Government's coercive policies is attributed to the position that many Mennonites took by 1922.

The conflicts over military service and education during World War I led to a subsequent emigration of Mennonites from Canada to South American nations like Paraguay and Mexico in 1922. Even more emigrated after World War II.

First Nations, Métis and Mennonite People Have Things in Common

So all three people groups (First Nations, Métis and Mennonite) had at least three things in common:

1) They each experienced attempts of the federal government to come up with a negotiated agreement to address their issues and concerns about the preservation of their linguistic, cultural and religious way of life, but in each case, the actual implementation of the Agreements came up far short of what was hoped for and expected. The Manitoba Act, Treaty No. 1 and the Mennonite Privilegium were never fully realized to the satisfaction of the people groups whose concerns that the Government was originally seeking to address.

2) They each had land-based economies and lifestyles that had learned to make a livelihood directly from the land, either from hunting, fishing or farming. Each culture had a deep connection to the land more so than to the government as their source of sustenance. They also each had a respect for the land, and a sense of responsibility to share the harvest with those who had less.

3) Each of these people groups also had a respect for the authority of the Creator, and had an inherent allegiance to the Creator's authority over the land that was over and above the political authority of the Government of Canada, and they saw themselves as stewards of the Creator. There was and is a spiritual side to their lives.

When Elijah Harper stated that "the political process has failed us," he could just as easily have said that "the religious process of the denominational churches has failed us." I knew Elijah Harper personally, and spoke at his funeral in May of 2013, and I know that when he stated that "what has been missing is the spiritual element," he was not referring to any need for another religious or political process.

Both politics in government and religion in denominational churches tend to exercise authority top-down, and enforce their rules and their laws by punishing those who disobey their policies and their edicts which they try to impose. A spiritual process, on the other hand, cannot be either coerced or imposed, because spirituality is a belief system that is written on the hearts of people, not with paper and ink. Spirituality is relational, and is a belief system about who the Creator is that cannot be imposed top-down.

Religious denominations used threats, and the fear of hell as a motivation to attend their particular denomination and to adhere to their particular religious beliefs. It was taught in way too many cases that that those who did not attend their particular denomination were going to hell. This is not necessarily true of all missionaries, but up in Pond Inlet, Nunavut, the Roman Catholics and the Anglicans had totally separate cemeteries, because they did not believe that they were going to the same place. This has caused many people to live under condemnation, and hence to not be able to flourish spiritually as the following statement attests.

What Elijah Harper was talking about cannot be legislated. Spirituality requires conversations about who the Creator is, and interactive dialogues in which all cultures acknowledge what is inherent in both the teachings of the Bible, and the Seven Teachings of Native Spirituality, all of which are spiritual values, namely Love, Respect, Courage, Honesty, Wisdom, Humility and Truth. As Elijah Harper described it, the vision of his forefathers and mothers was one that embraced Unity, Caring, Loving and Sharing. Land was seen as a gift from the Creator with the resources to be shared, not used for greed.

Based upon the genuine original teachings of the First Nations and Native American way of looking at life, consider the following statements by Chief Sitting Bull.

Elijah Harper would also talk about conversations that would lead to "a meeting of the minds." These sorts of discussions and conversations need to take place in a safe and a calm atmosphere about what we mean by spirituality, because spirituality is the fountainhead of culture, and culture is the fountainhead of politics, and politics is the fountainhead of legislation. One might raise legitimate question about this vision as to where the voice of the people will be who do not believe in a Creator at all, but who believe that the Creation or the world of impersonal Nature just created itself through a mindless process. Their voice needs to be welcomed at the table as well.

Just because we do not agree that there is a Creator who is personal, and who is Other than the Creation does not mean that we cannot have a relationship, or that we cannot respect each other's beliefs. The fact remains, however, that in order to be a healthy community, we need to have a healthy root system. We need to be open and respectful and open-minded in having discussions about our human origins, human beginnings, first principles that honour our common humanity. We need to accept each person for wherever they are at without using coercion, pressure or threats in order to attempt to change people.

Whatever one chooses to believe is a spiritual process. It needs to be said and to understood, however, that those who believe that Nature is a closed circle and that there is no spirituality that exists outside of the material world are not connected to the soil into which the roots of our community of Niverville have been planted. They are not connected to a root system that freely acknowledges the often hidden but spiritual dimensions of the roots that out of which our family tree has sprung. Just as a tree without roots is dead, a people without history or cultural roots also become a dead people.

In studying the history of our heritage, our roots and our ancestry in Niverville and surrounding areas, it is important to note that with three significant people groups that helped to formulate our history (First Nations, Métis and Mennonite), they not only had broken promises from the Government of Canada, but they were all people of faith. They all had a spiritual dimension to their lives, and all believed in the Creator of all, but they also had different viewpoints in both politics and religion to keep them divided, to keep them in isolation, and to keep them from communicating and having conversations with one another about our common roots in a Person rather than in non-personal substance. It is the indigenous peoples of the land, however, who have the most to teach us about the spiritual and the natural worlds being connected, and part of one reality.

(To be continued in part 2)

Comments

Post a Comment